What does this tell us about the character of our next winter here in the Pacific Northwest? More or less snow? More or less storms? Drought or wet? Warmer than normal or not? Let me tell you what we know.

As I have noted in previous blogs, El Ninos are associated with warmer than normal water in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. Think of the Pacific Basin as a big bathtub with warm water near the surface. The water is sloshing back and forth; when the warm bath water sloshes towards South America, you get an El Nino. Sloshes the other way, La Nina.

Babies and ducks have intuitive understanding of El Nino

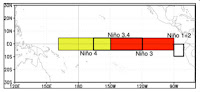

A plot of the sea surface temperatures in the Nino 3.4 and Nino 1+2 areas in the central and eastern Pacific, respectively, shows the story. Nino 3.4, in the central Pacific, is progressively warming-- now about 1.2C above normal. An El Nino is defined when the Nino 3.4 temps are more than .5C above normal for roughly a half year. But look at Nino 1+2! The eastern Pacific has warmed hugely, after being below normal late last winter. THAT is a major sign that the situation is very different from last year.

The U.S. (NOAA) has put in a network of buoys over the tropical Pacific (the TAO array) that tells us how warm the water is below the surface. These buoys show a huge increase in the heat content of the upper ocean in the central and eastern Pacific, as shown by the plot (below) of the upper ocean heat anomaly (difference from normal). The Pacific bathtub has really sloshed warm from the western to eastern Pacific!

NOAA and others have complex ocean/atmosphere models that can simulate the evolving El Nino. They are NOT perfect (as shown by their poor forecast last spring of a major El Nino that never materialized). But we are farther along in time and the uniformity of the predictions provides some confidence that their forecasts will be more skillful this year.

Here is the prediction from the NOAA Climate Forecast System (CFSv2) model for sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific (Nino 3.4 area) based on an ensemble of different CFS forecasts. All the forecasts are for warmer than normal conditions. NONE are going for cooler or normal.

Based on this and other forecasting systems, the U.S. Climate Prediction Center (CPC) produced a consensus forecast for the upcoming year (see below). 90% probability for an El Nino. They are going for it.

Strong El Ninos have a sea surface temperature anomaly (difference from normal) in the central Pacific of at least 1.5C. There appears to be an excellent chance we will achieve that. Keep in mind that we haven't seen a strong El Nino since 1997-1998 and that the global effects of that event were profound. For example, California had heavy precipitation with flooding and landslides that winter. In any case, we are sure to have at least a moderate El Nino.

So with a moderate to strong El Nino expected to be place for this coming winter, what can we expect here in the Northwest? To put it briefly:

1. bModestly elow normal precipitation

2. Warmer than normal temperatures

3. Less chance of lowland snow

4. Below-normal snowpack in the mountains

5. Less storminess, with reduced probabilities of major windstorms and floods.

But there are many subtleties here, including differing local impacts between moderate and strong El Ninos. This an important point missed in many media accounts. Let me show you the changes in impact as the strength of an El Nino increases. First, for precipitation,or more exactly, the precipitation anomalies (differences from normal).

Considering all El Ninos that meet the minimal requirements (.5C anomaly), western Oregon and Washington are dry---particularly the western slopes of the Cascades. California is wetter than normal.

Strong El Ninos are similar, with greater drying for the Northwest.

But then there are the super El Ninos, like 1997-1998 (see below) and they are different animals. California is VERY wet and above-normal precipitation extends into the Northwest, with the sole exception of the western slopes of the Cascades. If this happens, you can expect William Shatner to propose a big pipe to send water BACK to the Northwest.

What about temperature? This is a simpler story. Here are the temperature anomalies from climatology (normal) fro all El Ninos: modestly warmer than normal from eastern Washington to Minnesota.

Moderate El Ninos? The signal fades a bit.

Strong El Ninos enhance the warming a bit in the northern tier of states, but cooler than normal temperatures extend from California eastward.

Super strong El Ninos? Very warm from the Northwest eastward, with the warmest anomalies in the Upper Plains and Midwest. A fine winter to visit the sites in North Dakota or northern Minnesota.

Big windstorms? The plot show the timing of the really big windstorms (red dots) versus tropical sea surface temperatures. Big windstorms AVOID strong El Nino years. Similar to vampires and garlic. But there can be moderate storms in El Nino year and it appears that the very strongest years (like 97-98) had plenty of coastal storms.

Clearly, warmer than normal temperatures accompanying the strongest El Nino's is bad for snow over our region. Snowpack is generally reduced in the Cascades, but not "end of the world" reduced. Amar Andalkar did a nice study of this issue, finding a 10 % decline in Cascade snowpack for weak El Nino years and 15-20% for strong El Nino years. This is FAR better than what we had last winter (75% reduction). So the Cascade snowpack may be below normal but will undoubtedly be much better than last year!

Strong El Nino years also tend to have less major arctic outbreaks extending over western Washington and Oregon--good news for those worried about cold sensitive plants.

The bottom line is that El Nino, and particularly a strong El Nino, heavily weights the atmospheric dice for a less stormy, warmer, and a bit drier Pacific Northwest. But nothing is certain and the impacts will depend on whether the El Nino ends up moderate or super strong.

The real importance is not about the Northwest. Rather, will this El Nino bring enough precipitation to California to pull them out of their historic drought? They desperately need the water. And El Nino years normally bring far less Atlantic hurricane activity, which is a benefit to the coastal areas of the Gulf and the Atlantic coast. And strong El Ninos produce a net GLOBAL warming, so expect the upcoming year to break many heat global heat records.

No comments:

Post a Comment